This blog was co-authored by Kristen De Peña and Kelly A. Sanders, senior consultants, management consulting, Altarum Institute.

Flash back to the brink of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. On the cusp of the passage of the ACA, more than 41 million Americans were uninsured or underinsured, driving one of the largest health care overhauls in history. While controlling costs was an important consideration, the main focus of the ACA was expanding coverage. To increase accessibility to affordable health insurance options, the law employs a mixture of mandates, subsidies, tax credits, and penalties to increase coverage of the uninsured, spur health care innovation, and provide for new payment models to reward quality of care and improved health care outcomes.

More than five years into the ACA era, the White House touts that the number of people without health insurance continues to decline and has dropped by 15.8 million since 2013. Of the roughly 11 million people who enrolled in state or federal Marketplaces in 2015, about 4.2 million were auto-renewals or renewals, indicating that roughly half of all 2015 enrollees kept their 2014 Marketplace insurance plan.

The rurally ignored

Despite the widely publicized successes of the ACA, many rural Americans were forgotten by health care reform. Although the ACA proclaimed a renewed focus on rural America, little was accomplished for rural populations outside of Medicaid expansion. A policy brief published by the National Advisory Committee on Rural Health and Human Services stressed the importance of coverage in rural areas, where the population is disproportionately older, more chronically ill, lower in income, and less insured compared to urban areas.

Where are the rural communities? "Rural" encompasses all populations, housing, and territories not included in an urban area; essentially, it is defined by what it is not. In 2010, the U.S. Census estimated that 59.5 million people – 19.3 percent of the population – lived in rural areas.

Rural residents tend to be poorer, earning a per capita average income of $19,000, which is nearly $7,000 less than what their urban counterparts earn. Although rural Americans account for only 22 percent of the population, rural residents account for 31 percent of the nation's food stamp beneficiaries. Only 64 percent of rural residents are covered by private insurance, and the rural poor are less likely to be covered by Medicaid benefits than their urban counterparts (45 percent versus 49 percent, respectively). Compounding the issue of obtaining affordable coverage, rural areas rarely have access to the same types of coverage. According to the National Rural Health Association, only about 10 percent of physicians practice in rural America, even though nearly 25 percent of the population lives in rural areas. There are only 401 specialists per 100,000 people, compared to 910 in urban areas.

"Rural Americans face a unique combination of factors that create disparities in health care not found in urban areas. Economic factors, cultural and social differences, educational shortcomings, lack of recognition by legislators, and the sheer isolation of living in remote rural areas all conspire to impede rural Americans in their struggle to lead a normal, healthy life."

Perpetuated by the inability to find and afford care, rural populations face higher incidences of chronic disease. Obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and alcohol and substance abuse are all chronic conditions that disproportionately affect rural populations.

Turns out, chronic disease is costly

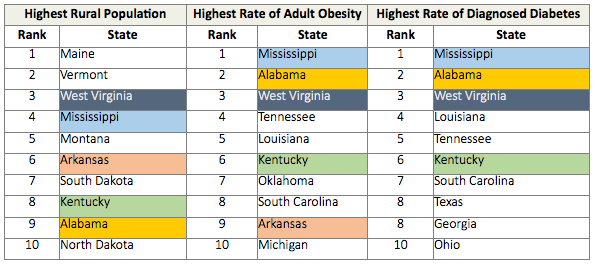

In the U.S., chronic diseases and the health risk behaviors that cause them account for highest health care costs. In fact, 86 percent of all health care spending in 2010 was for people with one or more chronic medical conditions. The total estimated cost of diagnosed diabetes in 2012 was $245 billion, including $176 billion in direct medical costs and $69 billion in decreased productivity. Medical costs linked to obesity were estimated to be $147 billion in 2008. Annual medical costs for people who are obese were $1,429 higher than those for people of normal weight in 2006. Of the top 10 states with the highest rural populations, half fell on the list of the states with the highest rates of adult obesity and diagnosed diabetes (Figure 1).

Figure 1: 2010 U.S. Census: States with the Highest Rural Populations Compared to States with the Highest Rates of Adult Obesity and Diagnosed Diabetes

So what is the government doing? Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recently awarded $2.7 million to improve rural health, however, those grants will support 3-year pilot programs designed to train health professionals and expand health insurance coverage in rural areas, rather than impact rural health directly. Essentially, the 20 recipients of the grants (ranging from $75,000 to $200,000) are community colleges, hospitals, health education centers, individual counties, and other various providers, which are to use the money for formal training programs for health professional students. To put it in perspective, HRSA responded to the outcry by millions of rural Americans by awarding grants equal to the price of 17-year-old Kylie Jenner's first home, after spending hundreds of millions of dollars implementing the ACA and federal and state Marketplaces.

Is telemedicine the perfect solution? Maybe

Although the ACA does not specifically link telemedicine to rural populations, "telehealth" or "telemedicine," which is using telecommunication and information technologies to provide clinical health care at a distance, is a critical component of transitioning to value-based treatments, and to better serving rural communities and chronic conditions.

For rural populations, telemedicine has the potential to increase accessibility to providers and specialists who can remotely monitor and treat chronic disease, without the hassle or costs associated with traveling. In many states, telemedicine services are covered by insurance to the same extent as in-person services. It helps eliminate distance barriers to medical services that would often not be consistently available in distant rural communities.

Although it seems like a catch-all, it is important to note that telemedicine is not a replacement for an annual, in-person physical; it is used most effectively to manage chronic condition and preventive health care costs. Even the best physicians in the world cannot take the blood pressure of a patient or press on the abdomen of a sick patient remotely. While certainly this represents a drawback, it also presents an opportunity. The rules governing the practice of medicine do not need to be the same rules that govern the practice of telemedicine. By linking patients with doctors either via telephone or video chat, barriers of distance can be eliminated, which proves crucial for rural areas.

Telemedicine snapshot: Mississippi

To address the prevalence of chronic conditions, Mississippi became the 16th state to pass advanced telemedicine provisions. In 2014, the American Telemedicine Association (ATA) graded existing state telemedicine programs based on reimbursement and physician practice standards, rating Mississippi with the highest possible composite score. Evidence of a collaborative landscape accommodating telemedicine, Mississippi requires telemedicine services to be a 'real-time' consultation, which does not include the use of audio-only telephone, email, or fax. Additionally, the Mississippi legislature also required that telemedicine services are covered to the same extent as in-person services, although a health plan may limit the number of telemedicine providers to a local network.

With the highest prevalence of adult obesity and diabetes in the country, Mississippi prioritized remote patient monitoring services to coordinate primary, acute, behavioral, and long-term social service needs for high-need, high-cost patients. For telemedicine services to be reimbursed, patients must be eligible for remote patient monitoring and specific patient criteria must be met. For example, qualifying patients for remote patient monitoring must be recommended by their physician, be diagnosed in the last 18 months with a chronic condition like diabetes or heart disease, and have a history of costly services because of that condition.

Initial barriers to telemedicine implementation

Although Mississippi has faced relatively little resistance incorporating these laws, many states still need to consider a number of issues or barriers when developing telemedicine programs and policy.

1. Requiring coverage for telemedicine under private insurance, state employee health plans, and public assistance

Reimbursement continues to be a barrier to telemedicine adoption in some states. Medicare, which typically sets reimbursement standards, reimburses for telehealth services with relatively stringent requirements. Medicare pays for telemedicine services only when patients live in Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs) and those who engage in "face-to-face" interactive video consultation services and some store-and-forward applications (e.g., teleradiology, remote electrocardiogram applications). As stated in a report by the American Hospital Association, "Without adequate reimbursement and revenue streams, providers may face obstacles in investing in these technologies."

Plan administrators and providers need to work together to discuss telemedicine benefits and determine coverage options and reimbursement policies, similar to the Mississippi State Legislature passing a bill requiring private insurance to pay for telemedicine services at the same rate as it does for in-person care. States considering telemedicine will have to wrestle with similar decisions about what to cover (e.g., video consultations, asynchronous store-and-forward platforms, patient monitoring) and review technology guidelines that determine reimbursement eligibility to ensure maximum reimbursement. To put it simply, if providers are not getting paid, they cannot provide.

2. Patient consent and education

Consent is a vital component of health care and is more complicated with a telemedicine platform. States must consider requirements for how to approach and obtain patient consent. The risk of consent-based claims for providers is a concern, and malpractice laws are currently geared toward face-to-face interactions; if consent-based claims become rampant, the willingness of providers to administer health care via telemedicine will likely decrease. Nebraska, for example, requires written informed consent, while California and Arizona law permit verbal consent to satisfy the statutory informed consent requirement. Since telehealth is a new and emerging field, patient education is critical to patients' health and providers' ability to practice.

Ideally, patients need to understand details about the expected risks and benefits of telemedicine, available alternatives, and how telemedicine fits into their personal wellness plan.

3. Geographical restrictions on telemedicine services

Although many states are ironing out provisions for health professional licensure requirements, including implementing special telemedicine licenses, border state and consultation exceptions, and interstate reciprocity and endorsements, little research has been done regarding restrictions on limitations for patient location while receiving telehealth services. For instance, can a patient on vacation in another state or country meet with his or her physician for an appointment? If the physician prescribes medication, can the patient fill his or her prescription outside of state lines?

Consideration needs to be placed on not just where the provider is operating from but also where the patient is located at the time of treatment and how treatment is administered.

4. Establishing the provider-patient relationship

Trust is an essential factor in a provider-patient relationship. It has been historically built during face-to-face interactions. States need to consider whether an in-person examination component is necessary or telemedicine can be used instead of an initial in-person patient evaluation.

The face of health care is changing, but prioritizing relationships is at the core of what creates value and better outcomes in health care. When implementing telemedicine programs, it is essential to consider the health of the patient first and design an interaction model that will create the most effective patient-provider relationship.

Overwhelmed? Here's what we know, and where we're going. We know that there are a significant number of rural Americans in the U.S. who have a difficult time accessing and affording health care. We know that many of these Americans are the ones who really need it, given their higher incidence of chronic disease. We know that chronic disease costs a lot and that most rural Americans cannot afford to treat it conventionally. We know that on its face, telemedicine may be one solution to solving the problem of rural health care.

A continued focus on this population of Americans and a renewed sense of urgency will allow for thoughtful state legislation and progressive development. Using Mississippi as a model of telemedicine implementation that is more thorough than many of its counterparts, other states can review their successes and challenges, with specific focus on the issues identified in this piece. For instance, considering where a patient must be located to receive care from providers, as well where they are legally able to fill a prescription from that provider are critical considerations for every state developing and amending telemedicine laws. There are a number of stakeholders involved in the telemedicine field. To ensure comprehensive, thoughtful laws and reforms, state legislature should reach out to local health care providers, nonprofit research centers, state insurance and Medicare/Medicaid departments, private insurance companies, state legislators, and patients to evaluate needs and requirements, and implement suitable legislation.