Cybersecurity 'context' matters when protecting patient data, expert says

Information security teams use many tools to protect patient data and now a Vanderbilt University researcher said it’s time to add a new tactic for detecting inappropriate access to medical information.

“The industry needs to move beyond statistical anomaly detection – the count of accesses – and focus on the context of the access,” said Daniel Fabbri, assistant professor, biomedical informatics and computer science, at Vanderbilt University, and founder and CEO of Maize Analytics. “Moreover, there are tons of timing eccentricities to consider in healthcare that must be thought through. For example, a doctor sees a patient but does not write a note until 24 hours later.”

[Also: 10 stubborn cybersecurity myths, busted]

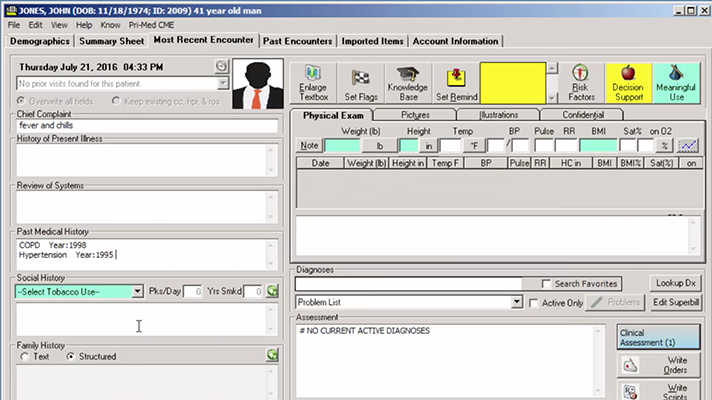

To begin with, it is important to understand the challenges of detecting inappropriate access to patient data in electronic health records systems. EHRs, for instance, generally have an open environment, which means employees can access any patient’s data after logging into the system. In practice, role-based access controls are limited.

“Further, employees are mostly well behaved,” Fabbri said. “Thus, occasional inappropriate accesses, snooping or identity theft, for example, are buried among normal treatment operations. Unlike other environments that treat a user as exclusively bad or good, in healthcare the user can be both good and bad on a single day.”

With these factors in mind, security approaches that look at the access login isolation, without clinical context, can only detect a few types of threats, and may even miss breaches, Fabbri explained.

[Also: Security giant McAfee to healthcare CIOs, CISOs: Know your enemy]

“First, because users have knowledge of the system, they can mimic standard workflows by clicking more to appear normal,” he said. “Second, EHR accesses are the observed effect of patient care, and to understand why those accesses occur, systems must incorporate clinical context surrounding an access in its prediction.”

Examples of that include appointments, labs, medications and others.

Basing detection models solely on what is observed (in other words: accesses) instead of the root cause (treatment) limits a model’s ability to differentiate appropriate and inappropriate access, he added.

[Also: Why diverse cybersecurity teams are better at understanding threats, patient needs]

As such, it is important for healthcare CIOs and CISOs to consider the threats they are trying to detect when selecting models to identify inappropriate use. If they choose a statistical anomaly detection model that identifies users accessing more records than normal, then it cannot detect one-off inappropriate accesses, such as snooping on a friend’s record.

“Other statistical anomaly detection systems attempt to identify ‘normal’ access patterns, and then alert on outliers,” Fabbri said. “The major challenge here is defining what is normal given the extremely dynamic nature of patient care, consultation services and constantly rotating clinical staff.”

One well-defined way to capture normal or appropriate behavior is to understand the clinical or operational reason why an access occurs. If there is a reason for the user to access a patient’s record, then the access is likely appropriate.

The clinical context necessary to make such a decision is already stored in the EHR and can be leveraged to infer why most EHR accesses occur. Any that do not have a reason is suspicious.

“The importance of context-based methods is that they not only tell you if an access is good or bad, but also the reason why, with the evidence for the decision, thus providing transparency rather than a black box,” Fabbri explained.

As Fabbri mentioned earlier, timing eccentricities in healthcare can mess with cybersecurity protection. But there are steps healthcare provider organizations can take to alleviate that.

“Ideally, all inappropriate access to health data would be detected immediately, or even prevented before they can occur; however, blocking access in healthcare can risk patient safety if, for example, a physician is unable to access a patient’s allergies in an emergency and then orders a medication the patient is allergic to,” Fabbri said. “Thus, organizations often focus on quick detection such as real-time auditing.”

Real-time auditing works well for a small list of VIPs, but real-time auditing systems can be susceptible to higher false-positive rates because the clinical context needed to infer why accesses occur does not show up in the EHR until after the access, he added.

“Near-real time auditing systems analyze accesses hours or a day later, thus utilizing additional context, which allows for more accurate detection,” Fabbri said. “Organizations must balance this trade-off between detection time and false-positives when developing their monitoring program.”

Twitter: @SiwickiHealthIT

Email the writer: bill.siwicki@himssmedia.com